Quality and technology IN CONSTRUCTION

delivered with STRAIGHT communication

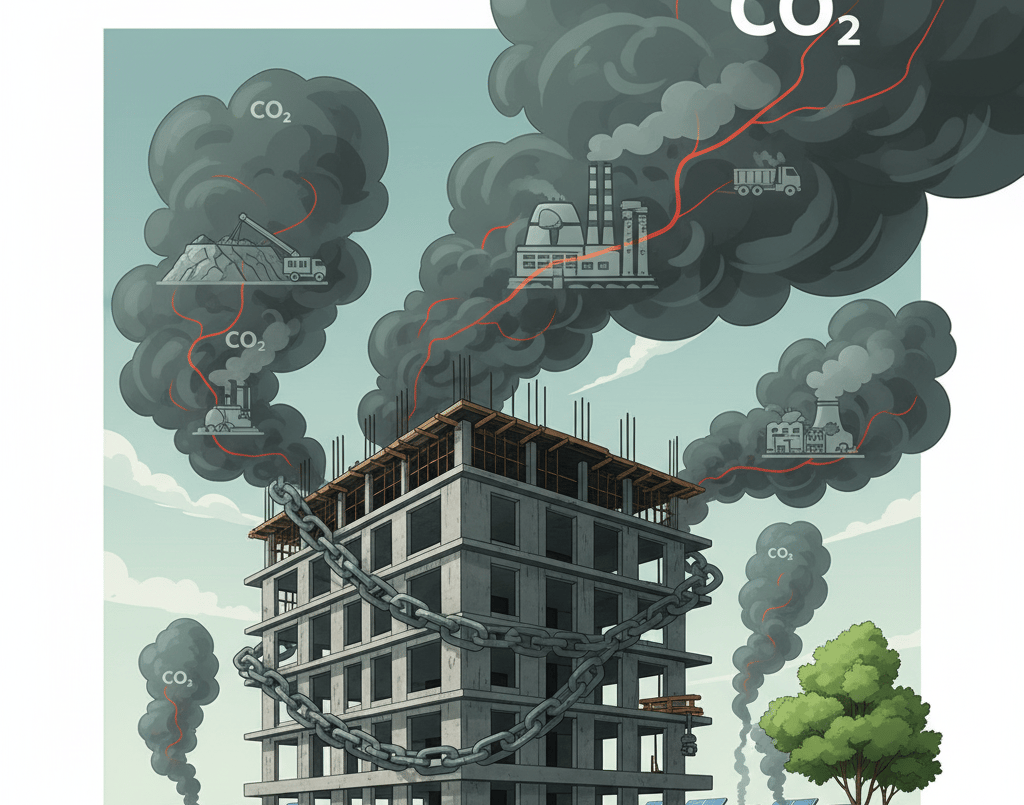

Embodied Carbon – the Invisible CO₂ We Lock into Our Buildings

Embodied carbon is the hidden CO₂ in construction, released during material production, transport, and building. It makes up 11% of global emissions and cannot be reduced later. Countries like the UK and Netherlands already act, while Hungary risks falling behind without life-cycle thinking.

CONSTRUCTIONTRENDPROJECTMANAGEMENTFUTURESUSTAINABILITY

Dr. Toldy Gábor - Toldy Construct

9/25/20252 min read

Embodied Carbon – the Invisible CO₂ We Lock into Our Buildings

When we look at a new building today, most people interpret energy efficiency only in terms of operation: better insulation, modern heating and cooling systems, solar panels on the roof. These are all important steps, but there is a massive, barely visible factor that the Hungarian professional and political discourse almost completely ignores: embodied carbon.

This is the CO₂ released before and during construction itself: from raw material extraction, processing, and transportation to manufacturing and building activities. It does not come from the building’s use phase, but from the fact that the structure is built in the first place.

The hidden polluter

Globally, the construction industry is responsible for almost 40% of annual CO₂ emissions. Of this, around 11% comes from embodied carbon – meaning the emissions are released long before the building even switches on its lights or heating system (World Green Building Council, 2019). This is a one-off but massive release into the atmosphere and – unlike operational emissions – it cannot later be “fixed” by solar panels or energy retrofits.

The construction sector is therefore not only an economic driver, but also one of the main engines of climate change. The question is not if we should deal with it, but how long we can afford to postpone addressing it.

International examples – where it is already taken seriously

United Kingdom:

The UK Green Building Council (UKGBC) requires life-cycle carbon assessments for larger projects. Developers cannot escape accountability: every step, from material choice to construction, must be quantified. This creates a clear line between genuinely sustainable projects and mere “greenwashed” PR efforts.

Netherlands:

Here, every new building must comply with the MPG (MilieuPrestatie Gebouwen) system, which evaluates environmental performance – including embodied carbon. The regulation is a strict market filter: if a developer cannot demonstrate low environmental impact, the project simply cannot be built. This approach effectively forces the industry onto a more sustainable path.

Hungary – trapped in short-term thinking

And what about Hungary? The focus of the construction industry remains short-term cost-cutting. Developers view insulation and reduced utility bills as the only “green” solutions, while the CO₂ emissions from material production and transport escape any form of control.

This strategy may look “efficient” on paper, but in reality, it is a double-edged sword: global trends – especially the EU’s mandatory carbon thresholds – will quickly put those players who fail to adopt full life-cycle thinking at a severe competitive disadvantage.

Conclusion

The issue of embodied carbon is not a matter of technology, but of political and strategic decision-making. Countries that acted early – like the UK and the Netherlands – are already gaining advantages, competing for leadership rather than survival in the regulatory environment of the future. Hungary, however, remains mesmerized by “cheap and fast” construction, undermining both its economy and its long-term prospects.

Sources

World Green Building Council (2019): Bringing Embodied Carbon Upfront

UK Green Building Council – Life Cycle Carbon Assessment Guidelines

Dutch Government – MPG (MilieuPrestatie Gebouwen) regulation

Construction

With over 20 years of experience in general contracting, our company specializes in the flawless execution of unique, bespoke buildings. Our innovative methods and mindset make us stand out in the market.

Our services

Contacts

company@toldyconsult.hu

+36 30 289 2383

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Our WEBPAGES

www.toldyconsult.hu